A mimetic system is a structure sustained by mimetic desire and the mimetic process.

The U.S. education and venture capital systems and almost every social media platform on the planet, are examples of mimetic systems of desire: mimetic desire sustains them. This kind of system has a motivational structure that keeps people trapped in deep mimetic grooves.

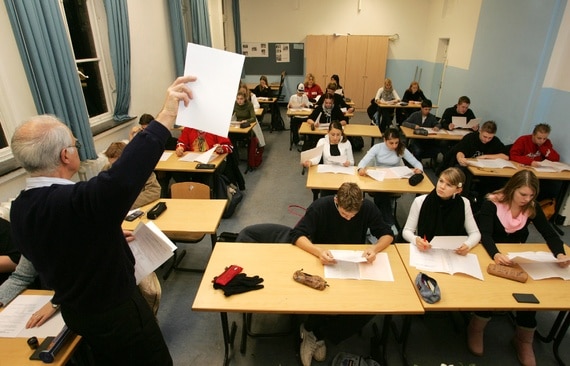

In the U.S. secondary schools, most students organize their energy around college application builders like their Grade Point Average, standardized test scores, and extracurricular activities. There is little mimetic validation in building one’s own business and delaying college, for instance. Indeed, most high schools have vicious metrics around 100% “college placement” which they use to fund-raise and shame any student who lowers the number—even if that student is making the best choice in their particular circumstances.

Moreover, as Peter Thiel has pointed out on Eric Weinstein’s podcast The Portal, most students have lost sight of the teleology, or purpose, of each stage of the education system.[i] When you’re in fifth grade, you know clearly that your goal is to get to sixth grade—and on and on, up through twelfth grade, at which point you’ve spent the past four years of your life preparing for something called “college,” along carefully defined lines (you probably even had a “college advisor” who advised you as to which schools you should apply for, based on your data.)

But college is where the teleology grows even less clear. Because current educational tracks are more of a mimetic system than a rational system, we’re not even framing the questions right. Instead of asking the question “Which college should you attend next year?” of high school seniors, some education entrepreneurs are re-framing the decision and asking, instead: “What’s the best way to spend this next year of your life, and to what end?” Which seems like a much better place to start.

Venture capital firms also operate in a mimetic system. VC’s need extraordinary returns on their investments to justify their existence—they often seek investments that can return 10x the value of their investment in the company, or which will provide a sufficient return for the entire fund even if every other investment fails. Therefore they favor technology companies that can scale quickly—not food service companies that might grow impressively but only incrementally over twenty or thirty years. VC’s typically need to realize their return in 5-10 years max.

This, in turn, increases the interest of entrepreneurs in tech startups (having a .com at the end of your name in the late 2000’s was a fool-proof way to raise significant money). A mimetic system takes shape. It’s important to realize that it’s not only due to economic incentives and financial returns—which no doubt factor in—but also due to mimetic incentives like the prestige, respect, and validation that comes with being financed by the right VC and, from a VC’s perspective, the headline grabbing companies and CEOs.

Social media platforms run on mimesis. Twitter encourages and measures imitation by showing how many times each post has been “retweeted.” People are more likely to use Facebook the more they are engaged with mimetic models and rivals whose posts they can track and comment on.

The greater the mimetic forces on a social media platform, the more people want to use it. If social media companies were to build-in more friction, or braking mechanisms for mimetic behavior, they would decrease user engagement and ultimately revenue. They have strong financial incentives to accelerate mimetic behavior. If two rivals are arguing back and forth on a social media platform, drawing others into the feud, it’s not hard to see who wins: the platform. Systems of desire positive and negative are everywhere. Prisons, monasteries, families, schools, and friend groups can all have them. And when a strong mimetic system is in place, it usually remains in place unless and until it gets disrupted by a stronger one.